Footprints of Italian Prisoners of War Project is a community project supported by Australians in six states and Italian families in sixteen countries.**

Did you know?

The website operates as a ‘virtual’ museum and library.

Over 300 articles have been written for the website.

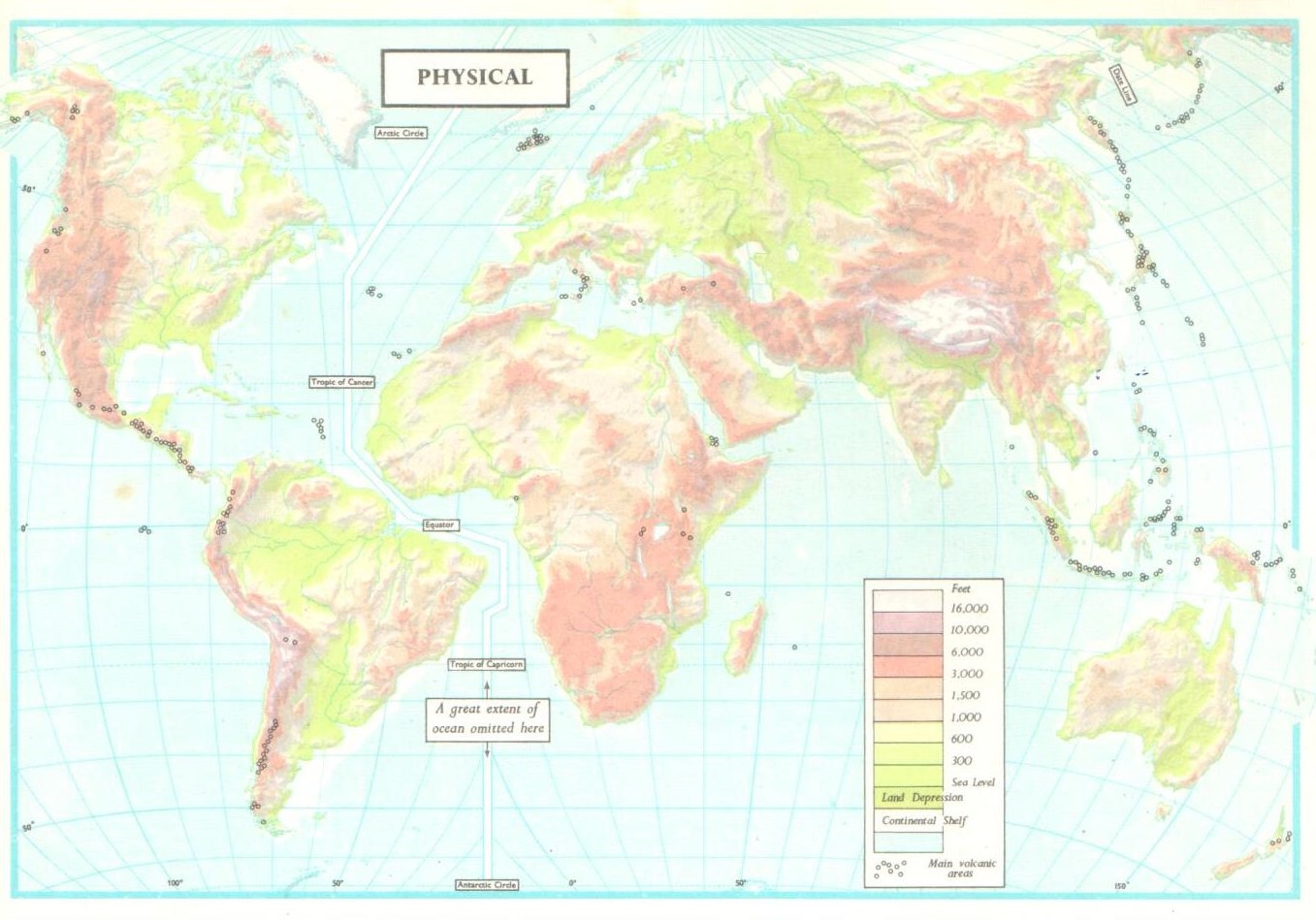

The website has a wide reaching readership to over 120 countries.

What makes this research unique and diverse?

Perspective.

Contributions have come from far and wide: farmers, farmers’ wives, farming children, the town kids, families of Australian Army interpreters, children of Italians who were prisoners of war, Italians who were prisoners of war, the local nurse, the mother of an ex-POW, government policy and reports.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

What does the research encompass?

Website: italianprisonersofwar.com

Facebook Page: Prigionieri di guerra Italiani in Australia

Music Book: Notations for songs and dance music by Ciccio Cipolla.

Farm Diary: daily notations regarding farm life during war time including information on Italian POWs and Land Army Girls.

Feature article in Corriere della Sera [Italy] in March 2021.

Memories in Concrete: Giuseppe Miraglia from Enna Sicily and Adriano Zagonara from Bagnara di Romagna Ravenna.

Donations to the Australian War Memorial of two artefacts made by Gympie Italian prisoners of war

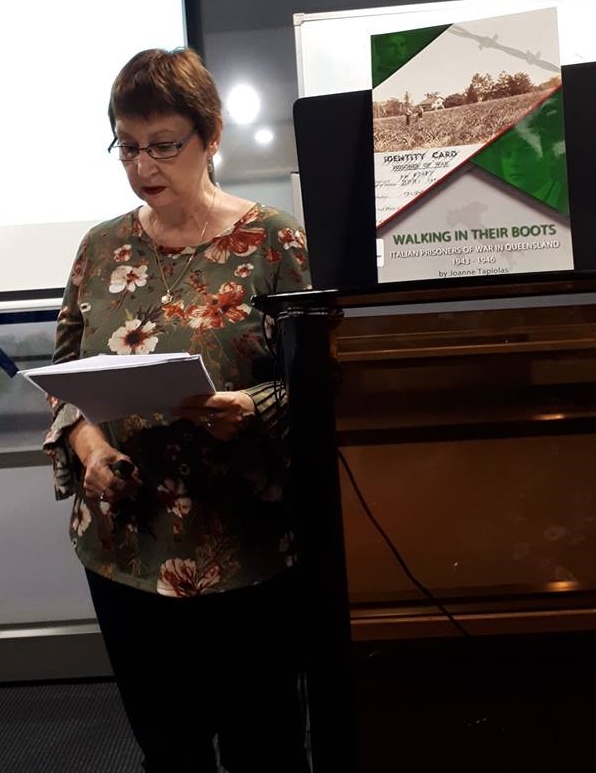

Two publications: Walking in their Boots and Costanzo Melino: Son of Anzano (in collaboration with Rosa Melino)

Journey of two Italian families from Italy to visit Queensland and ‘walk in the footsteps of their fathers’: Q1 Stanthorpe and Q6 Home Hill

POW Kit Bags: Adriano Zagonara and Sebastiano Di Campli

The Colour Magenta: The Australian prisoner of war uniform for Italians, Japanese and Germans.

Theatre Productions: Details of plays performed by the Italians

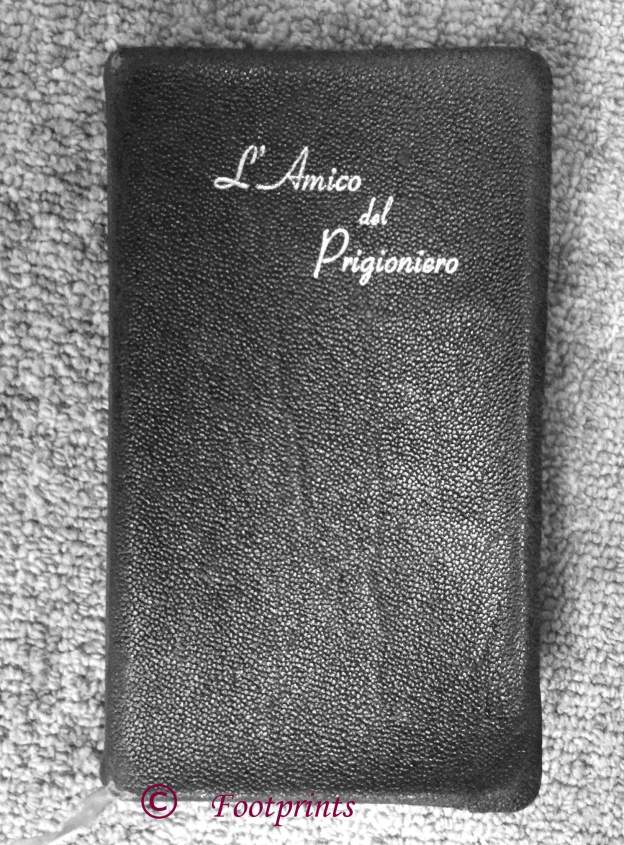

Handbooks: L’Amico del Prigioniero, Pidgin English for Italian Prisoners of War, Piccolo Guido per gli Italiani in Australia

Voices from the Past: testimonials from Italian soldiers who worked on farms.

Letters written by Italian prisoners of war to family in Italy, to their Queensland farmers and to the children of farmers, written by mother of an Italian POW to a Queensland nurse, written by the Italians to their interpreter, Queensland farmer to Italian, letters written between Italian POW places in different states.

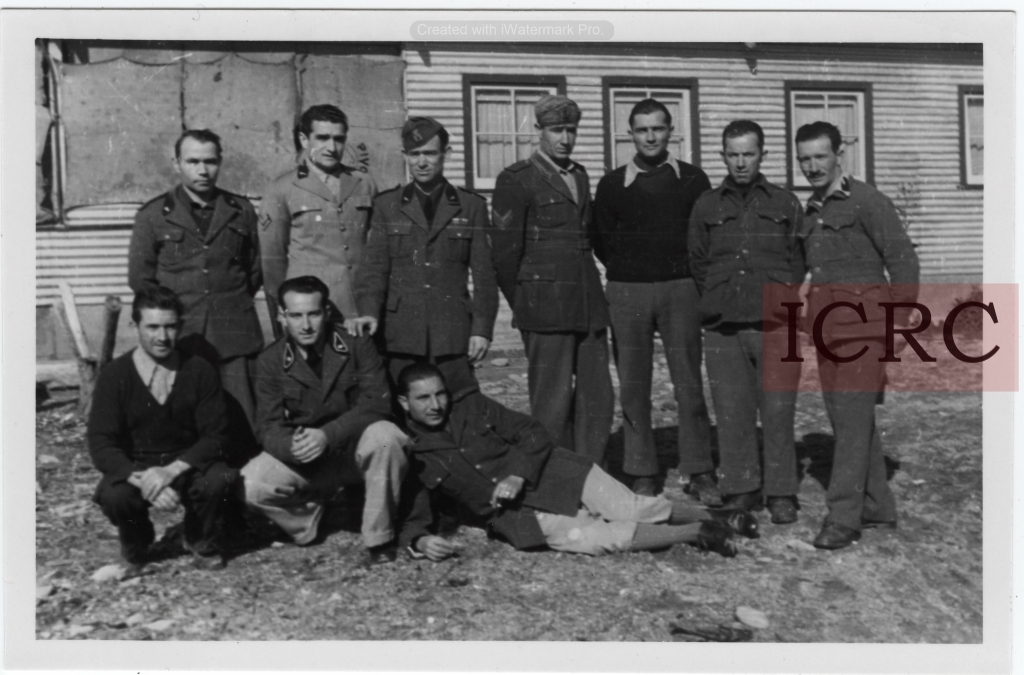

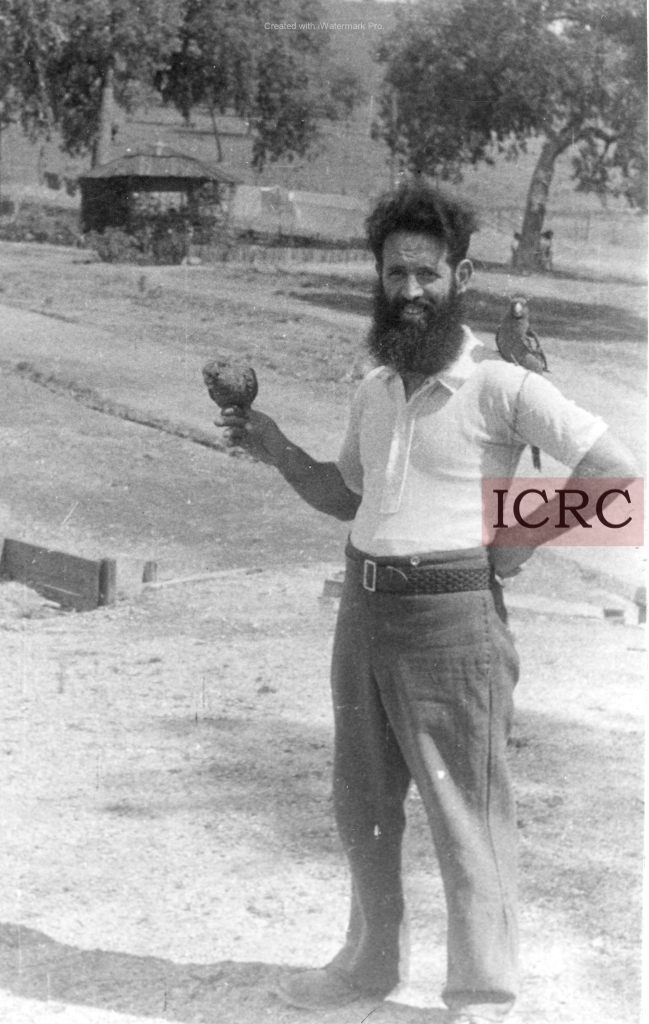

Photographs of Italian soldiers in full dress uniform, Italian soldiers in Italian and Libya during training, Italians as POWs with their farming families, Italians on their Wedding Day and with their families, Italians in POW camps in India.

Handmade items: embroideries, wooden objects, cellophane belt, silver rings, paintings, cane baskets, metal items, chess sets, art work, theatre programs.

Contributions by Italian families whose fathers and family returned to Australia as ‘new Australians’.

Identification of buildings used as prisoner of war accommodation.

Publication of three guides for Italian families to assist in their search for information about their fathers and grandfathers.

Collaboration with numerous Italian and Australian families; local museums and family history associations; journalists; translators; collectors of historic postal items; local libraries.

Discussion about our Queensland research at conference in Catania Sicily May 2019 on prisoner of war experiences.

My Wish List

In the beginning:

I had one wish, to find one Queensland family who remembered the Italians working and living on their farm. Thank you Althea Kleidon, you were the beginning with your photos and memories of Tony and Jimmy.

My adjusted wish list, to find three photographs of Italian POWs on Queensland farms. Then came Rosemary Watt and Pam Phillips with their collection of photos, a signature in concrete and a gift worked in metal.

….

Now:

To have the three Finding Nonno guides translated into Italian.

If I win Gold Lotto, to have Walking in their Boots translated into Italian or an upgrade to the website.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

**Background

What started out as a personal journey to read about the Italian POW Camp outside of Home Hill has resulted in a comprehensive, diverse and rich collection of stories, letters, photographs, testimonies, artefacts, music, newspaper articles spanning over 80 years: the battles in the Mediterranean and in Libya 1940 to the present.

Over the past seven years, I have heard these words many times over, “but you have it wrong, there were no Italian prisoners of war in Queensland”.

And this became a focal point for the research: to record this chapter in Queensland’s history before it was completely forgotten.

But like ripples in a pond, Queensland’s history of Italian POWs expanded across and was part of a greater history and so the project extended and expanded: to other Australia states and to Italian families in sixteen countries around the world.

Join the journey and follow the footprints of the Italian prisoners of war.